By Teresa Pitman

In 2008, 57 Canadians became ill after eating Maple Leaf deli meats contaminated with Listeria monocytogenes and 24 of them died. It was one of the most dramatic cases of foodborne illness in recent years. As director of Health Canada’s Bureau of Microbial Hazards, Jeff Farber was the Listeria expert who played a major role in leading the organization’s efforts in dealing with the situation. Farber worked with Maple Leaf Foods, shared information with the public, and helped develop new policies aimed at preventing or mitigating future outbreaks.

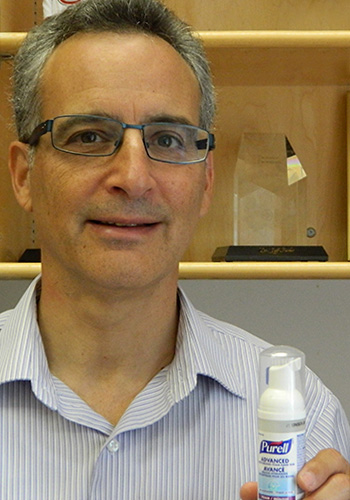

Farber received the Prime Minister’s Outstanding Achievement Award for his work during the crisis.

After 30 years working for Health Canada, Farber now brings his expertise in food safety to the University of Guelph as a faculty member in Food Science. In January 2016, as part of his appointment, he will also become director of the Centre for Research in Food Safety.

Farber has studied pathogens in dairy, produce, meat, fish and seafood, but more recently he has become interested in low-moisture foods. “We used to think that things like peanut butter, spices, seeds and nuts were unlikely to be hazards,” he says. “But now we are realizing that they can contain pathogens, too. There have been a number of outbreaks involving peanut butter, and we’ve recently seen Salmonella in a wide variety of tree nuts.”

He cites one example where contamination has caused serious issues: powdered infant formula. “For many years, nobody paid much attention to microbes in powdered infant formula,” he says. After several serious outbreaks in the 1980s, Cronobacter sakazakii was identified as the cause, and Farber says the formula industry has taken steps to reduce contamination. Still, the Centre for Disease Control reports about a dozen cases in the U.S. each year, and infection is often fatal in young infants, especially those born prematurely. Farber plans to research ways to prevent this.

Other areas of food safety research he intends to pursue: improving our understanding of Listeria; the potential for contamination of different types of nuts; novel inactivation strategies for pathogens in low-moisture foods; and the ecology of under-researched pathogens in fish and seafood.

Farber grew up in Montreal and attended McGill University. Although he initially studied medical microbiology and immunology, he moved to food microbiology for his PhD. “Food is so interesting — there are always new foods coming into the country and new production methods to investigate,” he says.

After graduation, he did a post-doc in a government lab in Ottawa studying mycotoxins, and was then offered a full-time position. “I had no intention of staying in Ottawa, but I ended up being there for 30 years.” He also taught as an adjunct professor at the University of Ottawa and brought students to work in his lab.

Working as a government director in food safety means a lot of pressure. “You barely have time to go to the washroom and you are on call seven days a week. You never know when or where the next outbreak or recall will happen,” he says.

Recognition of Farber’s work goes beyond Canadian borders. He was president of the International Association of Food Protection and was on the board for six years, and he’s also on the executive of the International Commission on Microbial Specifications for Food. His work with the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations led to a five-month stint studying many issues, including the safety of foods made out of insects — an important protein source in some African countries.

In his free time, Farber says he enjoys all sports (he organized a floor hockey league in Ottawa) and reading good books, mostly non-fiction. But teaching is a priority for him.

“I’m looking forward to helping train the next generation of food industry workers, scientists, inspectors and suppliers who will contribute to food safety,” he says.