The best kind of chocolate is creamy, smooth and melts in your mouth, not in your hands. Now University of Guelph food scientists say they have found a way to create that perfect chocolate that simplifies the traditional “tempering” process of repeatedly heating and cooling chocolate.

In a world first, a team led by food scientist Dr. Alejandro Marangoni discovered that adding a key component in cocoa butter fat to melted chocolate helps to hold it together and give it an ideal structure, simply and inexpensively.

Their discovery, which appears in the journal Nature Communications, could revolutionize how chocolate is made.

The research received coverage in the National Post, CTVNews.ca, the National Observer and several Spanish and German-language publications in Europe.

Creating chocolate that is glossy and snaps perfectly when broken is not easy. It requires “tempering” — a time-consuming process in which chocolate makers slowly heat and cool melted chocolate repeatedly to coax the fatty acid crystals in the cocoa butter into one stable form.

“If you’ve ever eaten bad chocolate, you’ll know it right away. It’s crumbly and grainy and soft. That is chocolate that has not been properly tempered,” said Marangoni, who holds the Canada Research Chair in Food, Health and Aging.

Typically, chocolate makers will employ “seeding” during the tempering process to encourage the chocolate to crystallize. The “seed” is often chunks or grated bits of already-tempered chocolate that act like magnets to attract loose crystals of fatty acids into line.

“A good chocolatier can do this by eye. Their experience tells them when the chocolate is ready, and they can make adjustments when it’s not. But that can’t be done in large-scale chocolate manufacturing,” said Marangoni.

Chocolate manufacturers use specialized equipment called tempering units, but even those aren’t foolproof, and manufacturers often find large variabilities between batches of cocoa butter.

Marangoni sought to make the process simpler by finding an ingredient that could more easily help form the correct crystal structure.

Along with research associate Dr. Saeed Ghazani, chemistry student Jay Chen and master of science student Jarvis Stobbs, he tested several “minor components” naturally present in cocoa butter and selected a specific molecule, a saturated phospholipid, to “seed” the formation of proper cocoa butter crystals.

Adding the phospholipid to melted chocolate and then rapidly cooling it once to 20 C accelerated crystallization without the need for tempering, the team found. The resulting chocolate had an optimal microstructure, with the ideal surface gloss and strength.

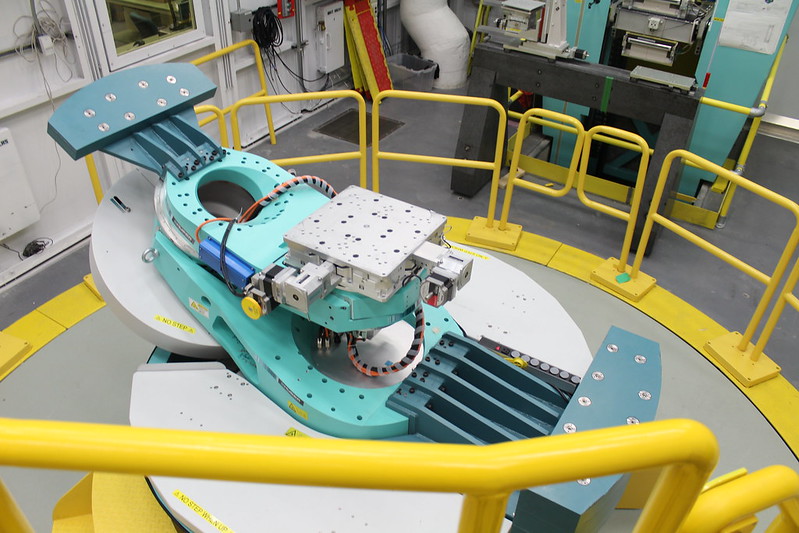

The researchers were able to confirm their finding by visiting the Canadian Light Source at the University of Saskatchewan, where Stobbs is a plant imaging lead.

The facility’s synchrotron technology and bright light — millions of times brighter than the sun — allowed the team to get micrograph images of the interior microstructure of their chocolate in full detail and confirm the positive effect their ingredient had on the chocolate structure.

“It’s exciting that you could just add a phospholipid — a natural component already present in the cocoa butter — to achieve the required tempering,” Marangoni said.

By potentially eliminating the need for complex tempering machines, he said, “this could revolutionize the industry and allow smaller manufacturers to produce chocolate without a big capital investment on machinery.”

This research was funded in part by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

Contact:

Dr. Alejandro Marangoni

amarango@uoguelph.ca