Remember the Walkerton water tragedy? U of G engineering professor Jana Levison certainly does.

In Walkerton, Ont., a dangerous strain of E. coli bacteria known as O157:H7 entered the town’s groundwater-supplied water system and because of mismanagement at the water treatment facilities, proper treatment and warnings were not provided. As a result, many people became ill and seven died.

The geological formation in the Walkerton area is a “fractured bedrock aquifer,” explains Levison. “That means that below the surface of the ground, there are tiny cracks and fractures in the rock through which water and any contaminants flow.”

To better understand the potential for contamination in these hydrogeological settings, Levison did her PhD research at a field site near Perth, Ont., where there is also a fractured bedrock aquifer below a thin layer of soil. “I monitored the changing concentrations of nitrate and E. coli spatially and over time, and connected the results to land use in the area,” she says. Land use is an important factor. Manure from livestock, for example, and human waste can contain dangerous bacteria.

In related research, Levison also studied how long it would take for dyed water from the ground surface to reach wells a certain distance away, and the types of chemical flame retardants found in groundwater.

“Basically, we discovered that in these sensitive aquifers contaminants can travel very quickly. The fractures are like little highways for contaminants,” Levison says. When she applied dyed water to the ground surface to see how quickly it would reach some nearby wells, she found that it reached the wells in just four hours. “If there had been thicker soil, rather than the fractured bedrock just under the surface, it probably would have taken much longer,” she says.

This matters because almost 30 per cent of Canadians rely on groundwater for their water supply; in rural areas the number is almost 100 per cent. The City of Guelph obtains its water from a fractured bedrock aquifer. “People don’t think much about where their water comes from or the effects of possible contaminants,” Levison points out, and this can be a significant issue for people in rural areas who get their water from private wells and may not test the water quality frequently.

Levison became passionate about water issues as an undergraduate studying civil engineering at Queen’s University. A three-month volunteer experience in Nicaragua, where she helped conduct an environmental assessment for a rural community well project demonstrated to her how essential the provision of clean safe water is.

After completing her PhD with Prof. Kent Novakowski at Queen’s University, she worked for the Professional Engineers Ontario in the Ontario Centre for Engineering and Public Policy. “The goal of the centre is to engage engineers in the development of public policy. I learned so much working there – it was really interesting and quite different from the research I had been doing. Yet there is a strong connection as well: there are many public policy implications that come out of my work on groundwater issues.”

In early 2011, Levison left that role and took up a post-doc position at the Université du Québec à Montréal with Prof. Marie Larocque in the Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences. The team studies groundwater-dependent ecosystems and the effects of climate change.

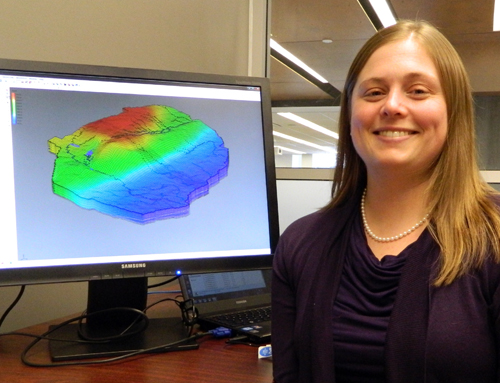

She was hired by U of G’s School of Engineering this summer and is part of G360: The Centre for Applied Groundwater Research under Prof. Beth Parker, director. Her current research involves field investigations and computer modelling of the effects of a variety of changes on groundwater quality and quantity.

“Our groundwater is generally very safe – in fact, Ontario is a leader in protecting groundwater in part because of the lessons learned in Walkerton – but we have to continue to take steps to make sure it stays that way,” says Levison. Changes in land use, increased urbanization, the use of road salt and the effects of climate change can all have an impact on groundwater quality and safety. She plans to focus her research on rural and agricultural water issues.

Levison also loves the teaching aspect of her professorial role. “It’s challenging and exciting to be working with students, and you know you are really making a contribution,” she says. Her family has a strong connection to U of G: both her parents attended the University in the 1970s, and her twin sister recently earned animal biology and veterinary degrees here. “It feels like home, and I like that you can be out in the country in five minutes,” she says.

Levison enjoyed riding horses and competed in eventing while growing up on her parents’ farm. Now she hikes country trails on foot, likes to cross-country ski in the winter, loves cooking and enjoys travel: she’s already been to Zimbabwe, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, the Caribbean and several European countries.