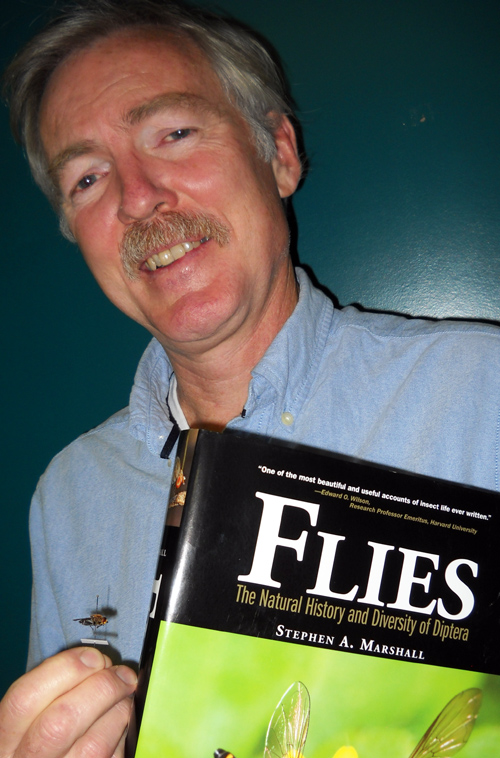

At home, Prof. Steve Marshall is as quick with a fly swatter as anyone. But as a U of G entomologist, he’s keener on flies than almost anybody you know. This fall he’s publishing a 600-plus-page book intended partly to show off the range and beauty of what Marshall calls “an enormously important slice of biodiversity.”

Mention flies and many people might think of death, filth and disease. Indeed, flies are arguably the most deadly insects on Earth, transmitting diseases that kill millions of people every year. Dipterans (“two wings”) also cause untold damage to forests, crops and stored products.

Where’s the beauty?

Marshall, a professor in the School of Environmental Sciences, says those problems are caused by only a few dozen fly species.

“Vastly more – thousands of species – are beneficial, contributing to the pollination of plants, biological control of pest insects, and disposal of the dung, carrion and other organic matter that would otherwise quickly carpet the planet,” he writes in his introduction to Flies: The Natural History and Diversity of Diptera.

As with his earlier award-winning volume – Insects: Their Natural History and Diversity, published in 2006 – this new book is published by Firefly Books. (How appropriate, you might think – except, as Marshall points out, fireflies are actually beetles.)

Flies covers the life history and diversity of the two-winged insects. The numbers are worth considering, especially for anyone whose fly savvy extends only to house flies, fruit flies, horse flies and maybe midges or gnats.

They’re only the beginning.

Scientists have discovered and described more than 160,000 species of flies, accounting for more than 10 per cent of named animal species. Add the estimated number of unnamed species on the planet, and you might be up to between 400,000 and 800,000 different kinds – and maybe closer to 20 per cent of life.

Among insects, only beetles are more diverse; biologists have identified about 400,000 coleopteran species so far and estimate about one million species in total.

But many beetles are more cryptic than ever-buzzing flies, says Marshall, which helps explain why you see more of the latter in your bug net, on your car windshield and around your picnic table.

“Anywhere in the world you go, the organisms you see are mostly flies,” says Marshall, a reformed beetle-maniac. Since switching from coleopterans to complete his master’s studies on seaweed-dwelling flies, he has spent most of three decades studying what he calls a neglected insect order.

“My lab group alone has discovered and named about 1,000 fly species. Flies are more interesting than damselflies, butterflies and beetles.”

(A handy taxonomic trick for keeping true flies separate from impostors: look for two words. House fly, horse fly, fruit fly: true dipterans. Butterflies, fireflies, dragonflies: eye-catching, yes, but, sadly, they’re not real flies.)

Next to their variety, it’s the wide-ranging and often bizarre behaviour exhibited by flies that attracts the Guelph scientist.

His book devotes a full chapter to the macabre lifestyles of parasitoid flies that eat other arthropods.

Ant-decapitating flies swoop down to lay their eggs behind an ant’s head. The fly larva eats the host from the inside out and exits, but not before administering the coup de grace: severing the ant’s head.

That gruesome trick might actually be useful for insect control efforts.

American biologists have used imported ant-decapitating flies to control harmful fire ants. By preventing the exotic fire ants from foraging for food, biologists hope to give harmless native ants a chance to out-compete them.

In the Tachinidae family are many members that lay their eggs inside other insects, often in creative ways worthy of a sci-fi thriller. Indeed, says Marshall, “The author of Alien almost certainly got his ideas from Tachinidae.”

He also outlines how flies carry real-life diseases that kill millions of people and untold numbers of livestock animals around the world. Chief among them is the Anopheles mosquito, a single genus that transmits the parasite that causes malaria.

Readers might be surprised to learn that mosquitoes are a kind of fly. They belong to the Culicidae, a family of midge-like insects. Mosquito is Spanish for “little fly.”

Flies contains a chapter on so-called “good” flies, including types that spend their days pollinating crops like canola in the shadow of bees – and even blend in by mimicking bees and wasps.

“Flies have historically been given short shrift in pollination studies,” says Marshall, who has worked with other researchers on the Canadian Pollination Initiative, a national group based at Guelph. “If you count up insects visiting flowers, the majority are flies.”

Among them are syrphids, such as a pair of jewel-like specimens he found on a mountain in Ecuador last year whose photo he chose to adorn his book cover. “They’re the most popular flies among amateur naturalists.”

The book also includes an extensive discussion of fly taxonomy, with more than 2,000 colour photos taken by the author and the first comprehensive key for identifying all of the dipteran families in the world. “This is the first generally accessible, illustrated overview of the order Diptera. For the first time, they are pulled together in one non-technical volume.”

At the same time, the book is not intended to stand alone. Marshall envisions readers using it to pinpoint families or sub-families of insects and then turning to more specialized resources to nail down individual genera or species.

An example of the latter is the Canadian Journal of Arthropod Identification, a web-based journal edited by Marshall. It covers insects as well as scorpions, crustaceans, spiders and centipedes. Recent online CJAI publications discuss Ontario fruit flies, pollinating cluster flies of North America and blow flies of eastern Canada, including species valuable to forensic scientists.

Marshall is also director of the U of G insect collection housed in the Bovey Building.

He began collecting bugs while growing up on College Avenue across from the campus dairy bush. He completed two degrees here and joined the U of G faculty in 1982. (His dad, Robert, was an agricultural economics professor here for about two decades.)

Steve Marshall’s bug forays have taken him around the world. Even Antarctica is home to insects, including midges. He has yet to check off Madagascar or New Guinea on his collector’s map.

One of his favourite destinations for fly diversity lies in the Pacific, off of South America. Not the Galapagos Islands – too dry for many flies, says Marshall. Try further south in the Juan Fernandez archipelago off of Chile, including Robinson Crusoe Island.

Besides having sustained a famous fictitious castaway – and the real-life marooned sailor Alexander Selkirk – the tropical island is home to numerous insect species, including many found nowhere else on Earth.

Says Marshall, a two-time visitor to the island: “Eighty-five per cent of the flies there are endemic.”