During his lifetime, the playwright George Bernard Shaw was highly controversial. “He liked to expose what we think of as normal or right and, usually in a humorous way, show how illogical or arbitrary many of our most cherished ideas are,” says Dorothy Hadfield, an instructor in the School of English and Theatre Studies. It is perhaps that controversial aspect that has helped his plays stay popular for so long. As Hadfield says: “Many of the problems and issues he addressed still exist; his plays seem eerily contemporary.”

Not only have Shaw’s plays lasted over time, they’ve crossed borders and reached audiences around the world. Some of those audiences will be gathering at the University of Guelph July 25 to 29 for the fourth International Shaw Society Conference entitled “Shaw Without Borders.” (See www.shawconference.org for more information.)

Hadfield, who is a member of the conference organizing committee, says registrations already include participants from Pakistan, India, Japan, New Zealand, Nigeria and many European countries. “We have a great mix of academics, students and non-academics. A large percentage of the society’s membership is just ordinary people who really admire Shaw and like to debate his works and ideas.”

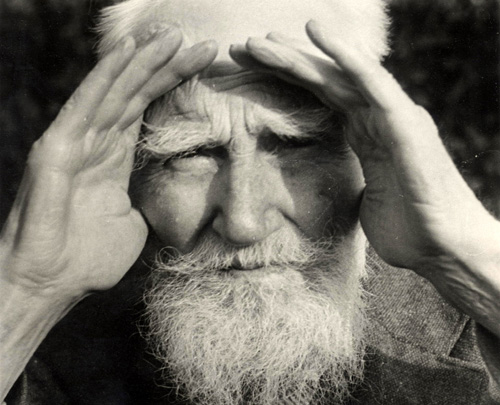

Why Guelph? Kathryn Harvey, head of archival and special collections at the University of Guelph Library, is chair of the local organizing committee and points out that the University is an important centre for Shaw research. “We have the official archives of the Shaw Festival, which is celebrating its 50th anniversary this year,” she says. “We also have the Dan Laurence collection.” Laurence was Shaw’s literary executor and provided memorabilia such as posters and programs from early productions of Shaw’s plays, letters Shaw wrote, and even a sample of hair cut from Shaw’s beard. “It was a very famous beard,” says Harvey.

Fitting the international theme of the conference, the library will also be displaying some translations of Shaw’s work. “We have a very good collection of Shaw in Japanese, Chinese, Hebrew and many European languages,” Harvey says.

The conference’s first full day happens to be Shaw’s 155th birthday, and the occasion will be celebrated with a birthday cake. Shaw generally disliked the idea of celebrating birthdays but the austere vegetarian was also tremendously fond of sweets and cakes.

The conference also provides the opportunity for two book launches, both open to the general public. The first, July 26 from 5:30 to 7 p.m. in the library’s Florence Partridge Room, is The Shaw Festival: The First 50 Years written by Leonard W. Conolly and commissioned by the Shaw Festival. “This book is really spectacular,” says Hadfield. “Conolly spoke to a lot of company members to get the inside stories, and there are colour photos of many of the productions.”

On July 28 from 4 to 5:30 p.m., The Prizefighter and the Playwright will be launched at the same location. This book by Jay Tunney, vice-president of the International Shaw Society, provides a new perspective on Shaw by describing his long friendship with Gene Tunney, the world heavyweight boxing champion from 1926 to 1928. Author Jay Tunney is Gene Tunney’s son, and his book includes many previously unpublished photos of Shaw.

Copies of both books will be for sale during the launches.

Another special event at the Shaw conference is a field trip to Niagara-on-the-Lake. Participants will be bussed to the Shaw Festival to hear current artistic director Jackie Maxwell and previous artistic director Christopher Newton speak, and then watch two Shaw plays: On the Rocks and Heartbreak House.

One session Hadfield is looking forward to will discuss copyright and censorship. During Shaw’s lifetime, he sometimes had difficulty in getting his plays produced – not because nobody wanted to see them, but because they contained such controversial ideas. “Censorship was a huge issue for him,” she explains. “At that time, all plays produced in Britain had to be licensed by the Lord Chamberlain’s reader, and several of Shaw’s plays were either refused licenses outright or had to be modified to satisfy the censor. Shaw actually spoke to a parliamentary commission about this issue.” The conference session will also discuss the legalities of presenting Shaw’s work now that his plays are out of copyright in Canada.

One of the plenary sessions entitled “Shaw and the Dictators” will look at what Hadfield describes as a more disturbing aspect of Shaw’s life ─ some statements he made during the Second World War that expressed sympathy for Mussolini and Stalin. This was controversial at the time and remains so today: a recent article in the Globe and Mail by J. Kelly Nestruck provides some background on the issue.

It may seem surprising that Shaw, an Irish-born playwright who lived most of his life in England (although he was, Hadfield points out, an avid traveller), should still appeal to an international audience many years after his death. Harvey says some of it may be the nature of plays. “A play is meant to be acted, so it is the infusion of the experiences of the actor, director and designer as well as the playwright that make up the performance. That adds richness to the framework and means that plays can reach broader audiences.” Add to that Shaw’s insights into topics common to all human relationships and you have work that continues to cross borders.