When Bill Macdonald was growing up in Guelph, his family’s old stone house had already become a go-to place for the brass from the colleges up the hill. They came to see his dad − or, more to the point, to have his dad see them. Some might have appeared more than once, donning their academic regalia each time to sit while Evan Macdonald wielded paints and brushes to capture their character on his canvas.

But on that late December day in 1970, it was only Bill. No presidential garments in sight; the closest thing to an ermine collar was the white fur trim on his parka hood. Then 20, Bill had just returned from forestry school in the Soo, a 12-hour train ride from the North back to Guelph. Hardly the best time for his dad to suggest posing for a portrait: “I’d just returned home from a long trip, that’s what was depressing.”

Forty years later, something of that funk shows in the subject’s distant blue eyes, his stubborn russet-covered chin and the set of his lips. Evan took only about half an hour, just long enough for Bill to down a beer while staring out the window.

Glancing at the painting propped on a chair in the front room of that stone house, Bill confesses he’s glad he yielded. “I think he saw the light in the window and he wanted to paint me.”

It might have been the last portrait Evan Macdonald ever painted, and one of the last pieces that the prolific Guelph artist completed at all. Evan had turned 65 that summer of 1970. In October, it had been his turn to visit the nearby campus to accept an honorary degree.

In 1972, Evan died after a nine-month illness. He left that 1850s stone farmhouse to his wife, Mary. She died in 1993 at age 85. Today Bill, 60, owns his childhood home; apart from that year in the Soo, he’s never lived anywhere else.

When his parents bought the house in 1947 at Edinburgh Road near College Avenue, it was still outside city limits. Now, tucked behind lilacs at the end of a gravel lane that Bill and his campus work buddies call “the road to Gunga Din,” it’s a Georgian farmhouse set amid a 1950s-era subdivision of brick bungalows and split-levels.

Inside, the symmetrical rooms and central hallway are lined with Evan’s work, a kind of personal gallery with Bill as curator. Look closely, and you can spot the hand of another artist – actually the hands of two artists.

As part of a nearly decade-long renovation project, Bill and his wife, Barbara Jean Shaw, expanded the studio that his dad had built at the back of the house. Rough pine board and batten, lots of windows, two skylights in the pine ceiling: it’s now about 500 square feet − plenty of room for two artists to work, hold occasional classes, even to eat meals at the folding tables.

The furnishings include a massive wall cabinet that was used to hold socks, shirts and ties in D.E. Macdonald Brothers, the family store formerly located in the Macdonald Block downtown before Evan closed it in the 1950s. Now the cabinet’s drawers hold art supplies for Bill and Barb, a retired schoolteacher and artist.

Bill also paints: more often in recent years. He works strictly in acrylic. No oils and nothing with solvents, not since they made him sick as an art student in Zavitz Hall.

After that year in the Soo, he had transferred to Guelph for a horticulture diploma and then pursued a fine art degree, completed here in 1978.

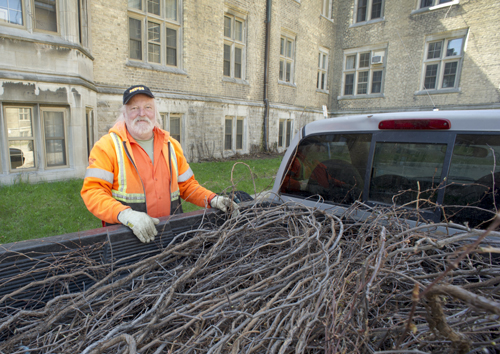

He’s worked at U of G ever since, first in several departments in the Ontario Agricultural College (OAC), then in physical resources. He was a residence porter but chafed in a cubicle. In 1988 he became a gardener in the grounds department.

In their studio this winter, he was beginning a painting of his sister’s cottage in Owen Sound and a landscape from the Bruce Peninsula, shapes roughed out on the canvas, lots of blues. “I love it up there, I’m absolutely drawn to that,” he says, recalling childhood vacations spent hiking and fishing from a cottage in Southampton on Lake Huron while Father was working.

Both Bill and Barb have sold works through Guelph’s Barber Gallery downtown. Gallery co-owner Mike Hayes, a former U of G classmate of Bill’s, says his work reflects his love of the landscape around home and on the Bruce Peninsula. “He paints mainly landscape from his own experience, places that he probably connects with very closely,” says Hayes.

So did Evan.

“They probably have the same inspiration,” says Hayes. “That’s what Evan was all about − recording landscapes that meant something. He was a recorder of history, almost like recording lost Ontario. He did a lot of paintings of buildings and architecture that have been demolished.”

Spend time at the Guelph Civic Museum or the Macdonald Stewart Art Centre (MSAC) on campus, and you’ll likely see evidence of that passion. Although Evan did numerous works on expeditions throughout Grey and Bruce counties − hundreds of pieces now occupy private collections across Canada − he often recorded streetscapes right here in town.

Through much of the 1950s and ’60s, he documented the loss of the city’s built heritage. Among his iconic works are oils of buildings in mid-destruction: the Guelph opera house, the former public library, the gas works, the customs house.

Many of his works – landscapes, streetscapes, portraits, people at work – still hang in the family’s stone house. Among them is what Bill calls his dad’s “flagship portrait” of Herbie Lawson, a well-known Guelph character who had worked at the Macdonald family store.

Before his recent renovations, even more of his father’s works had filled the house. “It was lying around like cordwood.”

Many of those pieces went to Bill’s older sister, Flora Macdonald Spencer, who lives in Dundas, Ont. An artist and teacher, she wrote Evan Macdonald: A Painter’s Life, published in 2008 during an MSAC exhibition of his work.

Flora remembers “busman’s holidays” with her father painting and sketching his way between the Maritimes and Lake Superior. She also recalls her father working at home, including the time when former Ontario premier George Drew visited for a sitting; that portrait now hangs in the Ontario legislature. Other artists visited the stone house, too, including Frank Panabaker and A.Y. Jackson.

Referring to the Macdonald family’s long history here − one ancestor worked for the Canada Company established in the early 1800s by Guelph founder John Galt − Flora says her father carried pride in his ancestral heritage and sadness at watching architectural icons fall beneath the wrecker’s ball.

In 2009, she and Bill donated a number of their father’s works to MSAC. Including their earlier donations and works acquired elsewhere, the gallery now has about 200 Evan Macdonalds in its permanent collection.

Referring to Evan’s painted record of the changing city, gallery co-ordinator Verne Harrison says, “He is part of the whole history, not only culture but the physical history of Guelph. He was one of the few people who made it big as an artist in the city.”

One of Harrison’s favourites is not a streetscape but a 1942 portrait of George Sydney Smith, a gunner who trained at the campus wireless school during the Second World War before being killed in Europe. Harrison sees the present and the future lingering in the portrait. “It was almost like a foreboding: ‘I’ve got to get this portrait done, because he’s not coming home.’ It’s almost frightening.”

Elsewhere around campus are other works, all identified by the artist’s signature in block capitals. They’re in the University Centre, War Memorial Hall, Alumni House, and the Pathobiology Building. Near the OAC offices in Johnston Hall, a Macdonald montage portrays most of the campus buildings of the 1930s.

Johnston Hall itself and the adjoining Johnston Green feature in a much larger painting located not far away. Visit Bill’s home base in the vehicle services building on Trent Lane, and poke your head into the office of grounds manager John Reinhart. Filling one wall is a mural recreating Johnston Hall and its environs, painted by Bill in 1994.

“I thought I could have fun with this,” says Bill. Gesturing around the office, he adds, “I wanted to go all the way around, but John wouldn’t let me do that.”

He’ll have to content himself with his after-hours work in that home studio-cum-gallery. Hung above the studio entrance is one of Bill’s own landscapes, showing the browns and greys of the campus dairy bush only a few minutes’ walk from the house.

Eyeing the piece, he says, “There’s a feeling of detachment from the madding crowd. That’s what I loved as a kid, going into the bush. I feel a frozen sense of time there. “I can almost feel history behind me. To me, that’s magic.”

That’s not all he feels, there in his − and his father’s − studio. “I feel that presence all the time. I remember how he would be standing at the canvas. I feel the presence of those memories.”