When a person is hired by an organization, there is not only a formal written contract that outlines expectations and responsibilities, there’s also a psychological contract on both sides. Psychological contracts consist of the obligations that employees believe their organization owes them and the obligations the employees believe they owe their organization in return. Each party engages in voluntary actions with the belief that the other party will reciprocate in return.

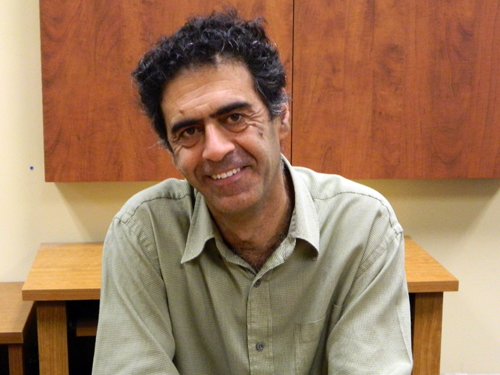

“If those psychological contracts are not fulfilled, employees are less satisfied and less likely to work as hard,” says Prof. Davar Rezania, chair of the Department of Business. “So it’s important for employers to pay attention to these unwritten contracts.”

Rezania is currently researching this from a slightly different context. “I’m looking at the psychological contract between student athletes and their team coaches,” he says. “How does the fulfillment of a psychological contract between coaching staff and student-athletes affect the team behaviour? Are athletes willing to try a little harder and do a little more when the psychological contract is fulfilled? My research suggests yes, there is an effect.”

The recently appointed chair brings a wealth of international experience to his role. Rezania was born in Iran and started university there, but moved to Turkey before graduation. A year later, he moved to the Netherlands and resumed his studies there, completing a degree in computer science. He found work as a programmer but was soon managing large-scale IT projects for organizations such as AEGON Insurance, Robobank International and ABN AMRO Bank. Many projects were international in scope: “I was working with people from the U.S., the U.K. and many other countries,” he says.

From the time he started in project management, Rezania was interested in understanding more about leadership. It wasn’t enough for him to succeed; he wanted to understand what was behind his success. “My teams performed very well and I wanted to know why. What was I doing right and how could I improve? I was doing a lot of coaching of younger project managers and wanted to understand how to help them, too.”

Seeking to improve his management skills, he completed an MBA while working at ABN AMRO Bank and then moved to the human resources department as assistant to the senior executive vice-president. “There I was working on HR strategy for the entire company and assisting with the plans for leadership development,” he says. That experience increased his desire to learn more, so Rezania went to Spain in 2004 to complete a PhD at ESADE Business School in Barcelona.

After graduation, he was hired by Grant MacEwan University in Edmonton. “I contributed to the development of the bachelor of commerce program at Grant MacEwan,” says Rezania, “and for the last three years, I was the chair. We had 1,600 students in the program, and it continues to do very well.” He came to U of G in August.

Rezania says his passion for research and understanding effective management has made the shift into academia an easy one for him. He also has an interest in research on how students are taught about business and has published papers about experiential classroom learning for business students.

He recalls speaking to a friend he had worked with in the Netherlands who said: “You’ve turned your hobby into your work.” Now Rezania thinks that may be a recipe for a satisfying career.

His wife is also from the Netherlands, and they are settling into life in Guelph with their two young children. Both parents are interested in environmental issues and appreciate that these are valued here. “We live close to the river and my children have enjoyed exploring,” says Rezania.

As department chair, he will spend a considerable amount of time on administrative work, but he looks forward to teaching next term. “I really enjoy teaching. I even received the distinguished teaching award last year at Grant MacEwan. I like to challenge my students. Sometimes they complain a little, but they appreciate it,” he says.