Playwright Colleen Murphy says she has “a conflicted relationship with the theatre. I love it, and I wrestle with it.”

In fact, she was so exasperated by how her first play, All Other Destinations are Cancelled, was produced by Toronto’s Tarragon Theatre that she left the world of theatre for a decade. “I very much disagreed with the interpretation of the production,” she says. “That premier presentation is the first impression people get of the play; it sets the tone.”

Despite the challenges, Murphy couldn’t stay away from theatre forever. “I love the stage.”

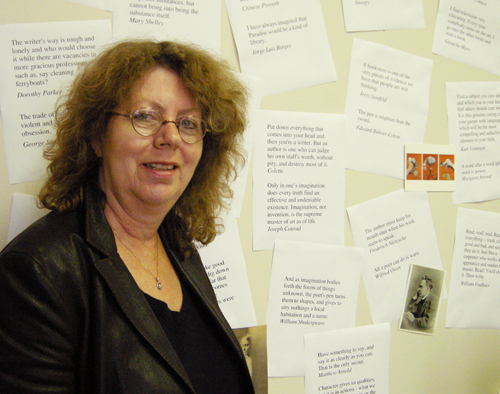

She’s sharing her enthusiasm for drama and writing with the University community as this semester’s writer-in-residence. While her specialty is writing text-based plays for the stage and screenplays for film, she’s also interested in short stories. Writers can leave manuscripts with Michael Boterman, secretary for the School of English and Theatre Studies; he’ll pass them on to Murphy and set up an appointment.

Murphy will also give a public presentation on tragedy Oct.12 from 11:30 a.m. to 1 p.m. in Lower Massey Hall. Called “Confronting Ourselves: Writing Tragedy in a Godless World,” the presentation uses the history and structure of tragedy to frame readings of three of Murphy’s new plays.

“Tragedy is not about awful things,” she adds. “It’s about human motivation and human responsibility. I am fascinated by it.”

Murphy’s love for the stage pushed her first in front of the audience; she studied acting at Ryerson University and at the Strasberg Institute in New York. “I realized that I was very interested in the construction of character and the action of the play, more so than performing the play. It wasn’t really a big leap. As an actor, you have to understand the psychology of the character, and it’s a very small distance from there to being intrigued by how the writer creates the characters,” she says.

Her radio drama Fire Engine Red won third prize in the CBC Literary Competition in 1985; that same year she joined the playwrights unit at Tarragon Theatre.

Whether she wrote for film or stage, Murphy continued to accumulate awards. She won second place in the 1990 CBC competition with Pumpkin Eaters and was nominated for a Genie for best screenplay for Termini Station. She was also nominated for Genie awards for other films: The Feeler, Shoemaker and Desire. Murphy worked at times with her husband, well-known documentary film-maker Allan King, who died in 2009.

In 1996, back in the world of theatre, Murphy’s play Beating Heart Cadaver was nominated for a Chalmers Award and a Governor General’s Literary Award for drama. She’s continued to work in both film and theatre and won the 2007 Governor General’s Literary Award for English language drama, as well as the Canadian Author’s Association/Carol Bolt Award for drama for The December Man (L’homme de décembre).

Not satisfied with those accomplishments, Murphy began writing a libretto for an opera entitled The Enslavement and Liberation of Oksana G. Composer Aaron Gervais, a Canadian living in San Francisco, is writing the music. “The characters in this opera are fictional, but the research is true,” Murphy says. “It’s a tragic opera about a young Ukrainian girl who is lured into sex trafficking in 1997, and her struggle to return home.”

Murphy has completed the libretto and sections are being translated into different languages, since the musical score needs to be written to match the actual language the opera will be performed in; it has sections in Ukrainian, Russian and Italian as well as English.

While working here as writer-in-residence, Murphy will be finishing a play called Deliver Me. “It’s set in Carthage in 250 AD, and it examines the idea that all religions end in blood,” she explains. “The play is kind of a marriage between A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum and Euripides. It’s funny but also tragic, exploring the clash between the Roman pagan cults and Christianity.”

She’s also working on two other plays: one about a woman from Vancouver’s East Side and her murder on a pig farm outside the city, and another play about a Canadian soldier who has just returned from Afghanistan. “It’s not an anti-war play and it’s not a pro-war play,” Murphy says. “It’s about honour.”

This prolific writer has no difficulty coming up with new topics. “My plays are not introspective; I am more inclined to look out than in,” she says. “The ideas and themes come to me just from living in the world and the times we live in.” She finds theatre a great medium for life-and-death issues. “All the great playwrights have looked at big things: how do we face death, how do we face life, what happens when family falls apart?”

Despite the tough economic times, Murphy sees Canadian theatre as healthy. “There’s always tension between the need for the theatre to make money by filling the seats and the need to be provocative enough to really compel audiences,” she says. “Right now, theatre’s not quite as fit as a 21-year-old athlete; it’s more like a 50-year-old with a few bad habits. But it’s not on an oxygen machine yet. Far from it.”