Dad, this spud’s for you.

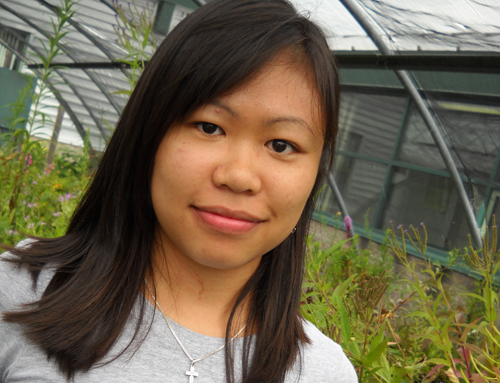

That might be a line for Stephanie Bach, a Guelph grad student in plant agriculture looking for more healthful potato varieties. Not only do her grandparents have Type 2 diabetes, but her father back in Edmonton learned last year that he also has the disease.

“I was already in Guelph when my dad was diagnosed,” says Bach. “Every family has health problems. This is close to me.”

That family connection has helped put a human face on her efforts to find spuds that will help stem such growing health problems as obesity and diabetes. Working with Prof. Al Sullivan, she’s beginning her second year of master’s studies, looking at potatoes inside and out.

Her work combines lab-based plant breeding and genetics with test plots grown across Canada. Looking at genetics as well as growing conditions ─ an approach labelled “genotype by environment” ─ is intended to help pinpoint varieties that yield lots of potatoes for growers and pack more healthful nutrients for consumers, she explains.

She says potatoes have yet to fully recover from bad press several years ago. Those reports tagged spuds as fattening and bad for your health ─ not the full story, according to Bach.

Like other plant foods, potatoes contain different kinds of starch. In the body, some of those starches are rapidly broken down and cause blood sugar to spike about 20 minutes after you eat them. Those starches have a high glycemic index (GI). Other starches with a lower glycemic index release their sugars at a more moderate rate. Still other starches are highly resistant and make up fibre.

Finding potatoes with a more healthful mix of those starches ─ especially lower proportions of rapidly digestible starch ─ is Bach’s goal. She says slow-release starches in a range of foods might help to prevent or moderate Type 2 diabetes, which is usually developed later in life.

She spoke about starch and health during the annual potato research field day held this month at the Elora Research Station. Organized by research technician Vanessa Currie, the event showcased new varieties grown this year at Elora and various studies by potato researchers, including U of G members.

Bach tends field plots at Elora. She’s also studying potatoes grown in Alliston and Simcoe, Ont., and in New Brunswick, Manitoba and Alberta. For those out-of-province sites, she works with private growers and partners in Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC), who ship their spuds to Guelph for her studies.

Her potato plants have come from the AAFC potato breeding program in New Brunswick. She also breeds potatoes on a smaller scale here. Using traditional breeding tools, she hopes to find high-yielding plants whose potatoes contain more healthful forms of starch and fibre.

It’s a challenge.

“Potato genetics is quite complex.” Unlike, say, humans with their two copies of genetic material, potatoes carry four copies of every gene. But Bach says that complexity is what holds out promise for new varieties.

She’ll begin harvesting in mid-September. Among her tests, she’ll boil the spuds in the department’s kitchen lab, then freeze-dry and grind them to flour to analyze their starch content. That involves running the flour through a simulated digestive system and monitoring glucose release.

Results from last year’s field studies already show differing effects of both genetics and varied growing locations, she says, including significant differences in rapidly digestible starch in potatoes grown in her three Ontario sites.

Currie says Bach’s study “will help breeders in developing new potato varieties that have low GI in addition to strong agronomic traits like yield, disease resistance and culinary quality.”

Bach studied genetics at the University of Alberta before coming to Guelph last year. “This department is the best in the country in terms of agriculture,” she says. Besides working with Sullivan, she’s collaborating with other researchers here in food science and in animal and poultry science, and with nutritionists at the University of Toronto.