This article was originally published on The Conversation and got picked up by the National Post and Toronto.com

Childhood vaccination has long been a hot topic among parents, educators and health-care providers.

Concerns that an increasing number of parents are choosing not to vaccinate their kids recently motivated one school division in Canada to want to lobby the government of Manitoba to make vaccines mandatory for all schoolchildren.

In the end, Manitoba school boards voted overwhelmingly against the motion to lobby for mandatory vaccination. But the incident raises an interesting question about what the most successful methods are for promoting vaccination.

As a researcher in the history of medicine, I have written a book, with fellow public health scholars Bethany Philpott and Sara Wilmshurst about the history of public health campaigns in Canada. Our research reveals the effectiveness of such interventions in changing behaviours around vaccination.

The phenomenon of “Toxoid Week” was, for example, a major factor in the eradication of diphtheria — the first major childhood disease to be conquered through vaccination in Canada.

Until 1930, one in every seven or eight Canadian children got diphtheria. More children aged two to 14 died from diphtheria than any other disease.

In 1940, Toronto became the first city of over 500,000 people to go a year without any diphtheria deaths, thanks to this public health campaign.

A new diphtheria vaccine

Diphtheria has been all but forgotten today, but at the turn of the 20th century it was a leading cause of infant deaths. It is an infection that acts quickly. Children who fall ill can die within a week.

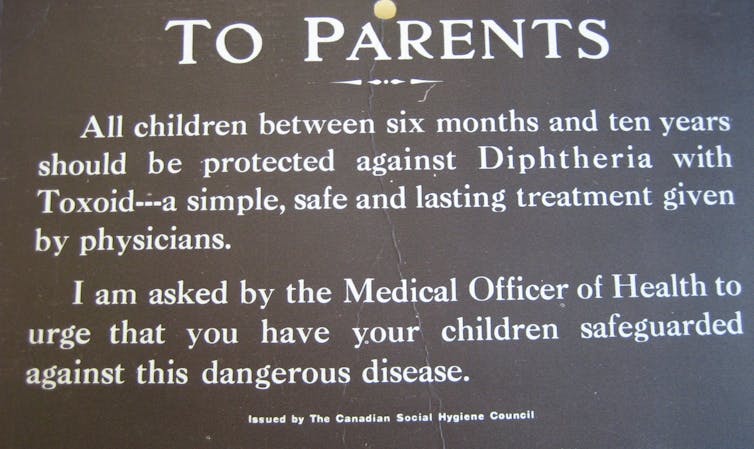

(Catherine Carstairs), Author provided

Symptoms start with a mild fever and sore throat, but eventually, a “diphtheric” membrane forms in the throat, which can suffocate a child. The disease also releases a toxin that sometimes harms other organs in the body, especially the heart.

A vaccine (toxoid) against diphtheria first became available in Toronto in 1926. Later, in 1931, the Toronto Diphtheria Committee was established to promote its use.

For the next 22 years, Torontonians would be cajoled, guilted and scolded into having their children vaccinated — with remarkable results.

The death rate in Toronto fell from a few dozen children a year in the early 1930s to none in 1940.

The annual ‘Toxoid Week’

The committee’s major focus was Toxoid Week, an annual April campaign. During the week, City Hall was adorned with an anti-diphtheria banner, and subway cars had placards promoting the vaccine.

Billboards across the city featured happy babies and slogans like “Parents…TOXOID prevents DIPHTHERIA.”

The three leading newspapers in Toronto published editorials urging parents to have their children vaccinated. Churches included announcements about Toxoid Week in their bulletins and clergy mentioned it in their sermons.

The committee convinced radio stations to run spot announcements and longer lectures, featuring doctors, aldermen and even the mayor.

At school, children used scribblers with printed messages on the importance of vaccinating against diphtheria. The committee provided teachers with cards and bookmarks listing immunization centres.

‘If your children die…’

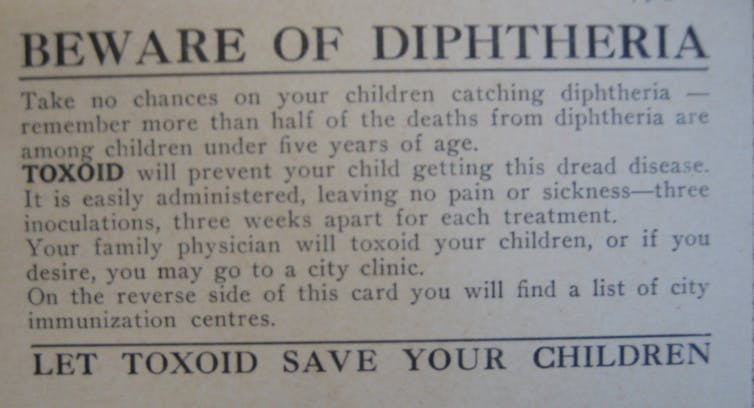

The Diphtheria Committee used guilt and hyperbole to get its message across.

In 1932, a radio talk for Toxoid Week blared: “If your children die of diphtheria, it is your fault because you prefer not to take the trouble to protect against it.”

Other talks emphasized the suffering of children with diphtheria: “One can imagine no more heartrending sight than this of a child struggling, fighting for breath, his little face gradually becoming darker as his blood is affected by the process, with death ever and ever nearer.”

One radio program asked: “Is your child toxoided? If not,” it scolded, “he is a definite menace to himself” and to other children. The talk compared the un-toxoided child to the spark that starts a raging forest fire.

Skyrocketing immunizations

Toxoid Week was a remarkable success. By the early 1930s, the incidence of diphtheria plummeted. In much of the rest of the country, where publicity was not as intense, diphtheria continued to be a problem.

In 1948, when Toronto had zero cases of diphtheria, there were still 900 cases of diphtheria nationwide.

The success of Toronto might be due to the extensive public health infrastructure compared to other regions. But there are some signs that Toxoid Week did make a difference.

When Toxoid Week began, the number of immunizations skyrocketed. Figures from the 1930s and early 1940s also suggest that children were significantly more likely to be vaccinated in the weeks after the campaign.

(Catherine Carstairs), Author provided

A survey undertaken by the Health League of Canada in 1947 indicated that more than half of the doctors believed that Toxoid Week led to more requests for vaccination.

Do we need another campaign?

It seems worth asking whether the tactics of shame and guilt employed were responsible for this success.

Could equally good results have been achieved from a campaign that stressed the benefits of toxoid, and assumed that parents would automatically do the best for their children, without the shame?

We will never know. But the annual publicity blitz did help to remind parents of the importance of having their children vaccinated. And the campaign greatly reduced childhood mortality and suffering.

Today, most Canadian parents do believe in getting their children vaccinated. A 2015 report from Statistics Canada, the Childhood National Immunization Coverage Survey, found that 97 per cent of parents believed that vaccines were safe and 98 per cent believed they were effective and important for their child’s health.

Results from the same survey show, however, that by two years of age, only 89 per cent of children were vaccinated against measles and only 77 per cent had received all four doses of the DPT (Diphtheria, Pertussis and Tetanus) vaccine.

If we wish to improve these vaccination rates, perhaps something like Toxoid Week — rather than the mandatory vaccination suggested by the Brandon School Division — could help?

![]() The statistics and quotations detailed in this article are all taken from archival sources. They are documented in the book Be Wise! Be Healthy! Morality and Citizenship in Canadian Public Health Campaigns.

The statistics and quotations detailed in this article are all taken from archival sources. They are documented in the book Be Wise! Be Healthy! Morality and Citizenship in Canadian Public Health Campaigns.