Editor’s note: This article was originally published on The Conversation and got picked up by the National Post.

Black Panther’s Erik Killmonger is the quintessential super-villain. His character fulfils the requirements of the typical superhero movie with good guys versus bad ones, and his demise at the end is inevitable.

How could we possibly find anything positive about him? Actually, there is much more to his character than just evil. In fact, I think his character has a lot to teach us.

Many critics have highlighted his killings, his CIA connection and his imperialist power lust. They focus on his bloody trail of slaughter and his destruction of the magical flowers that energize the spirit of Wakanda.

But consider his hate both for the oppressors of Black people and for the pretentious isolationism of Wakanda that cared nothing about Blacks elsewhere, and his plans of global insurgencies to liberate Black people.

While condemnation of Killmonger is to be expected, it’s unfortunate if it occludes his historical significance. Killmonger is larger, more complex and deserving of more nuanced appraisal. His character reflects the anger, frustrations, hopes, yearnings and aspirations of young and old African-Americans today.

Killmonger’s character represents the dialectical struggles – the complex history of debates and raucous disagreements among African American leaders – over their conflicting strategies and methods to win freedom from slavery, colonialism, racism and oppression.

Black liberation struggles

Killmonger shares a central and enduring goal with many previous Black leaders: the dream of freedom for his people and of righting injustices against them.

Consider abolitionist David Walker, who in 1830, against the prevailing gradualism of the abolitionist movement, circulated an appeal for Blacks to resist their oppressors with violence. He argued that kidnappers and murderers of Black people were enemies of God whose death when being resisted was justified.

In an argument similar to Walker’s, abolitionist and minister Henry Highland Garnet in 1843 informed his fellow Blacks how sinful it was for them to submit to degradation and oppression, to “a state of slavery where you cannot obey the commandments of the Sovereign of the universe.” Calling for a violent rebellion, he contended it was the Blacks’ “solemn and imperative duty to use every means both, moral, intellectual, and physical, that promises success.”

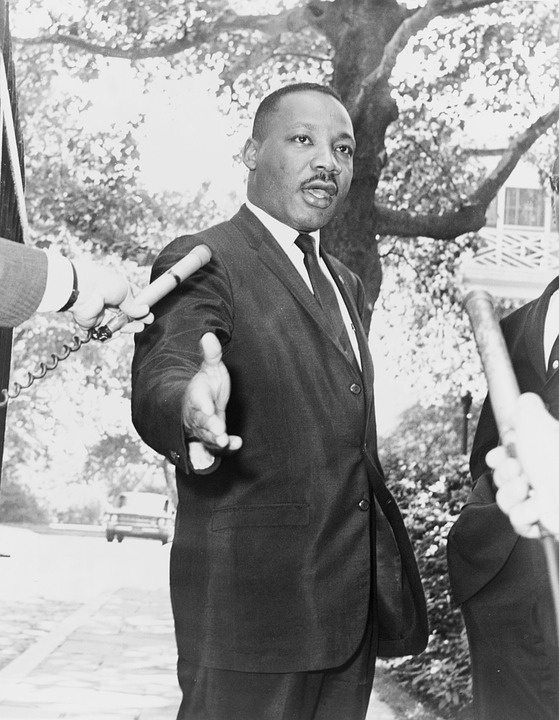

(University of Chicago Photographic Archive, (apf1-08637), Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library)

Frederick Douglass opposed this view and at the 1843 National Convention of Colored Citizens narrowly won the majority vote against it. Soon though, Douglass shifted his position to favour the use of direct action against slavery while maintaining his belief in the unity of the United States.

Frustrated by government abdication of its duty to protect Blacks from the Jim Crow lynchings, the famous Ida B. Wells urged that “…a rifle should have a place of honour in every Black home, and it should be used for that protection which the law refuses to give.”

Killmonger reflects his environment

As a special op in the U.S. army, Killmonger, née N’Jadaka (but also known as Erik Stevens), mastered the use of the rifle. There is a significant revolutionary symbolism to all this. Ida B. Wells applauded Black men who avoided being lynched because they armed themselves with the Winchester rifle.

Killmonger’s adoption of the violent revolutionary method also parallels revolutionary philosopher and Pan-Africanist Frantz Fanon. Both of their experiences participating as soldiers in violent national liberation struggles shaped their dispositions to consider violence instrumental to physical and psychological liberation.

Erik Stevens grew up an orphan, experienced tough inner-city teen life and suffered racism and oppression. He was also roiled by what he felt was the needlessness of Blacks’ sufferings as he was aware of the technologically advanced Black Wakanda and their isolationist policy of not intervening to liberate other Blacks.

Killmonger responds to a history which tyrannized him and left him with no hope of remedy. His choice of method reflects his environment and his association with working class and unemployed Black people.

Like Marcus Garvey, the radical Black nationalist and pan-Africanist leader of UNIA, a back-to-Africa movement, Killmonger envisions an African empire led by technologically advanced Wakanda that straddles the Atlantic and that sends out liberation squads to turn the table of hegemony on the powers that oppress the Blacks.

Garvey, who pioneered this inverted hegemony idea, was vilified as a lunatic and dangerous by the popular Black leader W.E.B. Du Bois.

Nevertheless, Garvey was ahead of other Black leaders of his time in rousing the popular masses, gaining their allegiance and devising cross-continental structures and ventures to help in his audacious plans to create an economically self-sufficient and militarily powerful Black empire to liberate all Blacks.

We should also note that Killmonger operated only within a delimited historical moment. He is not absolute. His choice of method cannot be the absolute solution either.

Remember Malcolm X and MLK

Neither Malcolm X nor Martin Luther King Jr. and their choices of method for liberation achieved that status either. Indeed, both contradictorily held aspects of the other’s strategy. Malcolm X came around to modify his strategy. He eventually accepted the unity of all oppressed across colour lines. Before his death, he manifested the possibility that hate and love could follow each other serially as underpinnings for liberation.

King, while maintaining his faith in “militant, powerful, massive non-violence,” said that he would not condemn civil right riots. King said “a riot is the language of the unheard” and that “America …has failed to hear that the promises of freedom and justice have not been met.” Even Mohandas K. Gandhi was emphatic that those unable to protect themselves by facing death with non-violence “may and ought to do so by violently dealing with the oppressor.”

Douglass before them also changed his position from advocating moral suasion to a more robust political activism and violent resistance to preserve freedom won by fugitive enslaved.

Thus, Killmonger’s character addresses the problem of Black liberation. His presence challenges the power of popular media and the hegemonic ruling opinion to dictate the acceptable methods to obtain Black freedom. The idea of Killmonger highlights the power of a global ethos to legitimate or delegitimate these choices.

The shallow development of Killmonger’s character in the movie subverts the universal scope of his liberation plans as well as his character’s ability to bring conversations of historical Black liberation figures together.

Black leaders and their revolutionary strategies like those of Booker T. Washington, W.E.B. Du Bois, South Africa’s ANC and PAC, Mandela’s Mkhonto we Sizwe, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. all accomplished transformations in their societies. Their methods, conflicting and sometimes contradictory, provided answers over a stretch of time to different aspects of the big problem of liberation.

Each method fulfilled its role at auspicious moments that supported its popularity among significant sections of the oppressed Blacks. The simultaneous relevance and application of these conflicting methods in those struggles is evidence that no single method was sufficient for the purpose.

![]() There has always been a Killmonger in the history of Black liberation struggles, and while history may not repeat itself, history often rhymes.

There has always been a Killmonger in the history of Black liberation struggles, and while history may not repeat itself, history often rhymes.